An Interesting Concurrency Bug

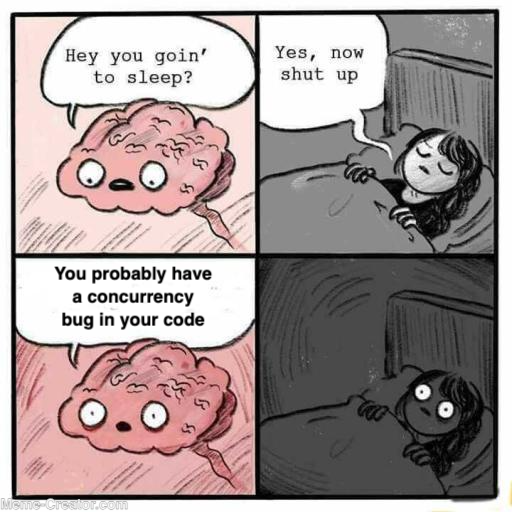

Concurrency bugs are perhaps the most insideous kind of bugs1. They’re sneaky, intermittent, hard to reproduce, and only like to announce themselves when and where you least expect (usually in production). However, that only makes them all the more interesting! Add to that the feeling of victory you get when you catch & solve one. So let’s see how I did that ;).

The Hunt

It all began when our sneaky concurrency bug kindly decided to reveal itself on CI, although somewhat coyly, while I was working on Methanol’s redis HTTP cache storage backend, through some HttpCacheTest failure. The failed test looked more or less like this:

@StoreParameterizedTest

void cacheGetWithMaxAge(Store store) throws Exception {

setUpCache(store);

server.enqueue(

new MockResponse()

.setBody("Pikachu")

.setHeader("Cache-Control", "max-age=2"));

verifyThat(send(serverUri))

.isCacheMiss()

.hasBody("Pikachu");

clock.advance(Duration.ofSeconds(1));

verifyThat(send(serverUri))

.isCacheHit()

.hasBody("Pikachu");

}

(yup, I use Pokémon names when testing, makes it fun!)

We’re testing basic cache behavior here. On first encounter, the cache forwards the request to network, and saves the response as it arrives. This results in an initial cache miss. Later on, we expected the response to be cached within its allowed time window (here it’s 2 seconds).

The above test failed with:

HttpCacheTest > cacheGetWithMaxAge(Store) > cacheGetWithMaxAge(Store)[3]: com.github.mizosoft.methanol.internal.cache.DiskStore@24018c8b FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

expected: "Pikachu"

but was: ""

... omitted stacktrace ...

Hmm, we’re getting an empty response body from cache. Looks like we’re either not saving the body properly or truncating it while reading. The cache has been around for more than a year, and I’ve never come across such a failure. Indeed, lamely staving this off as yet-another-flaky-test is attractive. However, I was determinted to find the cause, at least out of pure interest! This kind of bugs, however, are tough because you don’t exactly know where to look. Additionally, debuggers won’t help much2. However, we can start with pinning down potential cultprits:

DiskStore: This handles low-level storage of response data on disk.CacheWritingPublisher: Intercepts body flow from network and writes it as it’s consumed.CacheReadingPublisher: Reads the response body from cache on cache hits.CacheInterceptor: Decides, amongst other things, whether to forward the request to network or return a cached response if appropriate.

The trick is to know where to look first. We can overlook DiskStore for now as it basically wraps file IO using a simple layout (one file per entry). The interceptor has little to do with how data is actually read or written. CacheWritingPublisher & CacheReadingPublisher are the main suspects, particulary because they have involved concurrent implementations, so there’s a larger surface area for bugs. The former is less probable to be the cause than the latter, however, as reading the response body from network succeeds (as you can see from the first part in the test), which makes it likely that it has been fully written. CacheReadingPublisher is our main suspect! Let’s see how it’s structured.

Reading From Cache

CacheReadingPublisher is basically a producer and a consumer bundled together. The producer actively reads data from the store and dumps it into a queue till end of file is reached (with cool-downs if the consumer is slow).

The consumer polls data

from the queue and passes it downstream as requested3. As the consumer can be faster than the producer, it can perceive an

empty queue while data is being read. That’s why there’s a volatile boolean exhausted that’s set to true by the producer when it’s done,

so the consumer knows for sure no more data is expected and can go on to complete downstream when it sees an empty queue.

The producer and consumer are interleaved. There’s no syncyhronization between them aside from the implicit synchronization enforced by the queue (a happens-before between adding an item and polling it), and sharing exhausted. However, actions in each happen sequentually, in a quasi-single-threaded manner4.

The relevant consumer code looks(ed) like this:

@Override

protected long emit(Subscriber<? super ByteBuffer> downstream, long emit) {

ByteBuffer next;

long submitted = 0;

while (true) {

if (queue.isEmpty() && exhausted) {

cancelOnComplete(downstream);

return submitted;

} else if (submitted >= emit || (next = queue.poll()) == null) {

return submitted; // Exhausted demand or items.

} else if (submitOnNext(downstream, next)) {

submitted++;

} else {

return 0;

}

}

}

And this is producer’s callback after an asynchronous read:

private void onReadCompletion(

ByteBuffer buffer, @Nullable Integer read, @Nullable Throwable exception) {

assert read != null ^ exception != null;

// The subscription could've been cancelled while this read was in progress.

if (state == State.DONE) {

return;

}

if (exception != null) {

state = State.DONE;

listener.onReadFailure(exception);

fireOrKeepAliveOnError(exception);

} else if (read < 0) { // End of file.

state = State.DONE;

exhausted = true;

listener.onReadSuccess();

fireOrKeepAlive();

} else {

readQueue.offer(buffer.flip().asReadOnlyBuffer());

if (!tryScheduleRead(true) && STATE.compareAndSet(this, State.READING, State.IDLE)) {

// There might've been missed signals just before CASing to IDLE.

tryScheduleRead(false);

}

fireOrKeepAliveOnNext();

}

}

There’s a number of things happening here, but the relevant parts are setting exhausted = true and

readQueue.offer(...),

followed by fireOrKeepAlive[OnNext](). The latter basically ensures the consumer is up and running to see what we’ve produced.

Now give yourself a moment to find the bug! (hint: the culprit is the consumer).

The Bug

I like thinking about thread safety issues because most of the time it’s like a guessing game. You’re basically trying to work out scenarios that break your code. Indeed, there are more formal ways for proving correctness, but let’s now rely on our imagination and picture this scenario:

- The queue is now empty, and there’s an ongoing read.

- The consumer gets called and executes the

if (queue.isEmpty() && exhausted)part. queue.isEmpty()returns true, and just before testing (reading)exhausted, the consumer thread gets paused5.- The read completes, triggering another one that also completes (reads are triggered one after another upto a certain prefetch limit).

- The first read results in pushing a data buffer into the queue. The second read observes end of file and sets

exhaustedto true. - The consumer thread gets unpaused, and goes on testing

exhausted, which has just become true. - The test succeeds and the consumer completes downstream.

- Boom! A data buffer gets completely ignored.

Because our response in the test was small, this happened at the beginning, so we got an empty response body. Now give yourself a moment to come up with a simple fix! (hint: one hacky fix is to change only one statement in consumer code).

The Hacky Fix

Well, we can basically switch the testing order from if (queue.isEmpty() && exhausted) to if (exhausted && queue.isEmpty())6. This works because once exhausted is set to true, no more buffers are expected. That is, once exhausted is true, we’re bloody sure we’ve exhausted all buffers, and if we see an empty queue henceforth, that’ll be its final state, and it doesn’t matter whether, when, or where the thread gets paused.

Note that our main problem is Java’s lack of a closeable queue, which implies 3 states (non-empty, empty, closed) instead of two (non-empty, empty). In Go, for instance, we would’ve simply used a channel, which is basically a closeable BlockingQueue7.

A Better Fix

Having correctness rely on testing order is fragile. Interestingly, we only care about closing from one side: the producer8. We can use this fact to come up with a better fix using what’s fancily called sentinel values9. A sentinel value is basically a made-up constant that marks a certain event. We can create an empty buffer as a sentinel and add it to the queue when end of file is reached. This modifies producer’s code as follows:

private static final ByteBuffer SENTINEL = ByteBuffer.allocate(0);

private void onReadCompletion(

ByteBuffer buffer, @Nullable Integer read, @Nullable Throwable exception) {

...

if (exception != null) {

...

} else if (read < 0) { // End of file.

state = State.DONE;

queue.offer(SENTINEL);

listener.onReadSuccess();

fireOrKeepAlive();

} else {

...

}

}

And the consumer can confidently complete downstream when it sees that sentinel:

private @Nullable ByteBuffer lastNext;

@Override

protected long emit(Subscriber<? super ByteBuffer> downstream, long emit) {

// Pick up from where we left off.

var next = lastNext;

lastNext = null;

long submitted = 0;

while (true) {

// Poll prematurely to complete regardless of demand.

if (next == null) {

next = queue.poll();

}

if (next == SENTINEL) {

cancelOnComplete(downstream);

return submitted.

} else if (submitted >= emit || next == null) {

lastNext = next; // Save the last polled buffer, which might be non-null.

return submitted; // Exhausted demand or items.

} else if (submitOnNext(downstream, next)) {

next = null; // Consume.

submitted++;

} else {

return 0;

}

}

}

This’ll work because seeing SENTINEL strictly happens after seeing all the buffers pushed by the producer (due to the FIFO nature of the queue), so we won’t miss anything. Note that we had to store the last polled buffer10 as, in order to check for completion, we poll before checking downstream demand. So we might end up polling a buffer that hasn’t yet been requested.

-

Indeed, race conditions can sometimes be deadly, quite literally. ↩

-

Concurrency bugs are prime examples of Heisenbugs. ↩

-

Downstream is the resulting response, which is basically a reactive-streams subscriber. ↩

-

Which means that actions in each never interleave, although they may run in different threads at different times. See

AbstractSubscriptionto know how that’s done for the consumer. ↩ -

When you’re writing multi-threaded code, it is a healthy, although headache-inducing, practice to assume that threads can pause (i.e. get context-switched) when you least want them to. ↩

-

Normally, you wouldn’t think testing order in an

&&statement affects correctness, but our single-threaded assumptions are often broken when applied to multi-threaded programs. ↩ -

Indeed, the dawn of loom makes us less shy when mentioning things that block. ↩

-

Closing from the reader’s side can also be helpful as a way of saying to the producer, rather crudely, that we’re not interested in its stuff anymore. ↩

-

This is actually how I ended up fixing the bug. ↩

-

Recall that the consumer runs sequentially as if it is single-threaded, so we don’t need to use any synchronization for

lastNext(e.g.volatile). ↩